2008-03-08

John Lennon called him 'Normal'....

John Lennon called him 'Normal'.... (written by Julian Palacios)

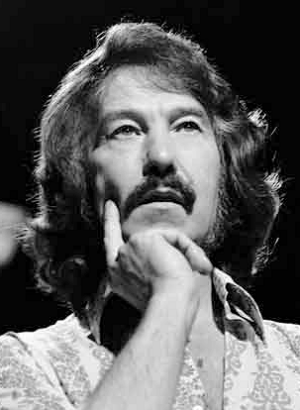

Norman ‘Hurricane’ Smith (February 22, 1923 – March 3, 2008) was part of the Golden Age at EMI. One of his very first assignments as engineer was the Johnny Kidd and the Pirates classic Shakin' All Over in 1960. Already in his thirties when he began with EMI, Smith came up through the ranks the hard way, learning the ins and outs of Abbey Road's three studios. By the time he got to engineering The Beatles, he'd already learned to compensate for the sometimes acoustically odd rooms and crude two track recording consoles.

He and others developed some extraordinary techniques; just listen to way Ringo's drums still jump out in She Loves You. EMI’s innovations left the competition baffled by their recordings, which couldn’t imagine Ringo Starr’s distinctive damped snare sound was due to a combination of close miking, compression and tea towels in the bass drum!

Smith had engineered all the Beatles albums through 1965’s Rubber Soul and was adept at the arduous cut-and-paste editing required for their four-track recordings. Having learnt his craft under the tutelage of Beatles’ producer George Martin, he had been promoted from engineer to producer and Piper was to be his first album as producer.

Norman and Pink Floyd

Despite his problems with Syd, (My godfathers, he's an awkward chap, this Syd Barrett) Smith did some incredible work with the Floyd, coaching them through vocal harmonies, sometimes joining in on the recording (Note). He, Peter Bown (engineer) and Jeff Jarratt (tape operator) rode the technological advances for all they were worth, using limiting and reverb, then moving into flanging, artificial double tracking. Spartan controls disguised the sensitivity of the circuits inside the desk. The TG12345 Curve Bender provided an equalisation curve, which let a sparkling surge of sound through to saturate the recording tape.

Smith’s touches were subtle but powerful, note the rising glissando note, which finishes each chorus on Bike, achieved using a crude oscillator and vari-speeding the tape down while the track was running. Smith was a hands-on producer, spending plenty of time on the studio floor with the band rather than ensconced up in the control booth.

Despite his at time stolid approach to recording, Smith had a wide-ranging ear and an experimental approach. If Mason wanted tympani, Waters wanted to play his bass with a violin bow or Wright wanted to mike up a harmonium, Smith was critical in helping them. Toy clockwork running around the studio floor or miking wooden blocks, these were all done because they had Smith as an ally.

Songs evoking the intensity of their live performances, such as Pow R. Toc H. and Interstellar Overdrive, benefited from Smith and Bown, having the rhythm section of Waters & Mason mixed right to the fore. The mono mix is much punchier, compressed so the midrange jumps out with thunderous drums and bass. If Barrett’s more intricate sonic textures fade into the mix, his guitar rings out sharp as sirens, jumping out like phantoms from under the stairs.

Stereo Piper

Despite purists crowing over the superiority of the mono mix of Piper, the stereo version Smith produced was a feat of engineering. So radical a departure from the mono mix, the stereo version amounts to the first remix album. Smith, in a dazzling display of work, did the entire stereo mix in two sessions totalling nine hours. The 2007 remaster gives the stereo The Piper at the Gates of Dawn great resonance, with a wide horizon of reverb, echo and chorus galore.

On the stereo version of Interstellar Overdrive, the rhythm section of Mason & Waters is mixed to the right, while the melodic team of Wright & Barrett is mixed to the left. The split in the stereo spectrum mirrors the split in the Pink Floyd’s own music; with an edginess that seeps into their tracks from the contention, musical and personal, between the two sides of the group.

Smith was working round the clock, doing double time on the Pink Floyd’s debut and The Pretty Things psychedelic song cycle S.F. Sorrow. Dick Taylor, the Pretty’s guitarist, recalled Smith as wide open to experimentation, and with Smith as producer the Pretty Things let loose with some inspired work. S.F. Sorrow and Piper DEFINE psychedelia, filled chock a brim with sonic invention. These Norman Smith productions sound radical and fresh forty years later.

THE MAN WAS A FUCKING MONUMENT!

Please, in memoriam for Hurricane Smith, crank up Interstellar Overdrive until your bass bins rattle and the council files a noise complaint. In Normanni nos fides. A great producer and one of the last of the old school. RIP old man, you will be missed.

(Written by Julian Palacios, reprinted with permission)

Update October 2014: a review of Norman Smith's memoirs can be found at: Hurricane over London.

Note: Norman Smith replaced drummer Nick Mason during the recording sessions for Remember A Day (October 1967, A Saucerful Of Secrets). His vocals are also prominent on the same track. Remember A Day is mostly cited as being one of the very few Five Man Floyd tracks (meaning that both Syd Barrett and David Gilmour played on the track, together with the rest of the band). Back to text.