Step It Up And Go

The following is a 'longread' about the blues musicians who gave Pink

Floyd its name.

Warning: inappropriate language is used

throughout.

TL;DR:

Syd Barrett did not have Pink Anderson and/or Floyd

Council records, as they were extremely rare.

Those two blues

musicians were named on the liner notes of a popular Blind Boy Fuller

compilation though.

It wasn't Syd who distilled the name 'Pink Floyd'

from that record, but Stephen Pyle, one of his friends.

Personnel: Trotting Sally | Simmie

Dooley | Pink Anderson | Samuel

Charters | Floyd Council | Bryan

Sinclair | Blind Boy Fuller | Warren

Dosanjh | Stephen Pyle

Review: Country

Blues, Blind Boy Fuller

Introduction

Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett fans have a pretty rough idea how the band acquired its name, although the exact story is probably less known and only interests Roger Keith Barrett anoraks anyway. In their enthusiasm, some fans even share pictures of the Pink Floyd name-givers on the dozens of, mostly obsolete and highly repetitive, Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Facebook fan groups, in their continuous race to be bigger than the others.

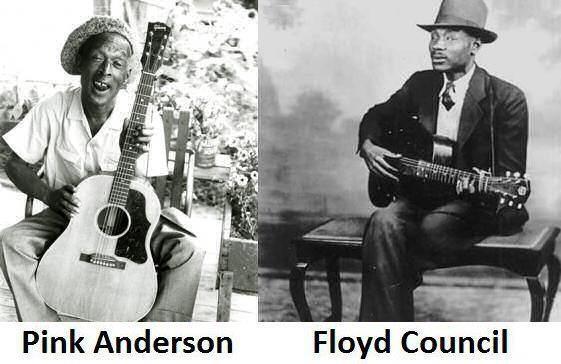

Here they are: Georgia blues singers Pink Anderson and Floyd Council, whose records were in the proud possession of a certain Cambridge boy.

Only, the person at the right is not Floyd Council, but Blind Boy Fuller (and they are not from Georgia either). We'll explain later how Blind Boy Fuller gets into the picture.

Knowing how a blues singer from the beginning of the past century looked like is one thing, knowing how he sounded often seems even more of a gargantuan task. And even the world's best music magazine wasn't so sure either.

Different tunes

The above YouTube movie allegedly has the Pink Anderson song C.C. and O Blues, followed by the Floyd Council track If You Don't Give Me What I Want. Only what you hear is not always what you get.

C.C. and O Blues

The vocals on C.C. And O Blues are from Simmie Dooley, not Pink Anderson. Dooley was a country blues street singer who lived in Spartanburg, South Carolina and who is mostly remembered as Anderson's musical mentor.

In the beginning of the past century Spartanburg's black district was named the politically incorrect Niggertown, by Negroes and whites alike. The black district was a spirited place, in all possible interpretations of the word, and not always safe to roam. Ira Tucker, lead singer of The Dixie Hummingbirds, remembers:

Anywhere you would go could be risky. Those guys in Spartanburg, they didn't take any tea for the fever. They would fight to the end!

As a black person, living in Spartanburg, one had to face thousands of indignities. The racist police was generally showing disrespect:

Nigger, you have to say 'mister' to me.

The black population of Spartanburg reacted, unsurprisingly, as expected.

The white cops, when they would get ready to arrest a black man, it would take three or four of them. If they came into a neighbourhood to arrest somebody for nothing, black people would fight back.

Not that a lot has changed a century later, with the exception that the n-word is now considered inopportune. USA police still can insult, kick and shoot unarmed black people, but as long as they don't call them N----- it's all passing by without consequences.

Trotting Sally

The black district of Spartanburg also offered good times and music was always around. Ira Tucker's grandfather 'Uncle Ed' was a musician who played a mean accordion and who sang in the local church choir.

Another character was Trotting Sally, real name: George Mullins. Born a slave in 1856, he was freed at the age of 9 and became a familiar street musician with his fiddle 'Rosalie'. He was known for his wild antics and crazy animal imitations. His behaviour was so eccentric that people doubted his mental stability. He was – literally - the stuff legends are made of. It was rumoured that Millins had superhuman strength, that he could outrun a train, hence the nickname Trotting Sally, and these heroic deeds were the subject of several late 19th-century folk-tales. When he died, in 1931, he was remembered in several newspaper articles. Although he was captured on film, no sound recordings of him exist. Ira Tucker:

He was an excellent violinist. Nothing but strings and his fingers. He had that violin almost sounding like it was talking. If you said “Good Morning”, he would make that violin say, “G-o-o-o-d M-o-o-o-rning”.

Simmie Dooley

Another street musician who not only impressed Ira Tucker, but Blind Gary Davis as well, was an old man who sang and played the guitar: Blind Simmie.

Simmie Dooley (1881-1961) may have played his favourite spot in Spartanburg's 'Short Wolford' when he met young lad Pink Anderson, an entertainer in a travelling medicine show who wanted to learn the guitar. They would go off in the woods to practice, usually with a bottle of corn whiskey 'to help the throats'. Simmie's educational system consisted of hitting Pink's hands with a switch until he got the chords right.

In search of Simmie

Anderson was not only Dooley's sideman, but also his eyes. It was practically impossible for a blind man to travel but with Pink he could go to the small towns around Spartanburg, like Woodroff and Roebuck, to play on country picnics and parties. They often performed together and in April 1928 they recorded four tracks for Columbia Records in Atlanta. These two 10 inch 78RPM records were issued under the name Pink Anderson and Simmie Dooley and have the duo at their finest. The musical bond between both was so strong that Pink Anderson refused to record without his teacher, which could have made his life much easier. (Apparently the record company didn't like Simmie's distinctive voice.)

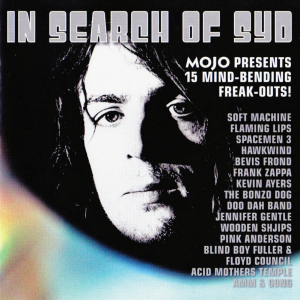

C.C. & O Blues, referring to the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railway that ran through Spartanburg, is a bit carelessly attributed to Pink Anderson on a Mojo cover disk of October 2007 (issue 167): In Search Of Syd. Simmie Dooley, who is the main performer, is only mentioned in the liner notes, but not on the front nor backside track-listing. It is one of those mysteries why exactly this track was chosen for the compilation. From that same 1928 session Mojo could have, for instance, picked Papa's Bout To Get Mad where Pink Anderson is the lead instead of Simmie Dooley. All in all there are about 3 dozen Pink Anderson songs but Mojo resolutely went for about the only track in his entire career where he can't be heard at all.

If You Don't Give Me What I Want

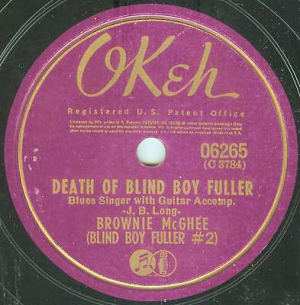

The second song on the YouTube movie from above is If You Don't Give Me What I Want. It can be found on the same Mojo compilation and there it is somewhat lavishly attributed to Blind Boy Fuller and Floyd Council. It certainly is a Blind Boy Fuller song, taken from a session in February 1937 with accompanying musicians Floyd Council (on guitar) and George Washington (on washboard), using the pseudonyms Dipper Boy Council and Bull City Red.

Mojo stretched the line by adding Floyd Council's name, making us wonder why they forgot the third musician. The YouTube uploader even went a step further by omitting Blind Boy Fuller from his own record, thus giving the title a self-explanatory extra dimension.

Although Floyd Council solo tracks are harder to find than those of Pink Anderson, they do exist and 6 of those have survived into the twenty-first century.

Ufonauts

If you are already confused by now, we can only promise it will get worse from now on. Who are these Pink and Floyd character everyone is talking about?

Syd Barrett at first tried to explain that the name Pink Floyd had come to him in a vision or by a passing flying saucer while he was meditating on a leyline, but the truth is somewhat less exotic. In a Swedish interview from September 1967, Barrett explained:

The name Pink Floyd comes from two blues singers from Georgia, USA – Pink Anderson and Floyd Council.

Basically this story kept repeating itself from article (for instance: Nick Kent, 1974) to article, from year to year, from biography to biography, without much checking of the journalists involved, although some did have the guts to add the odd detail here and there. But all in all it would take more than three decades to get to the truth.

In the Visual Documentary (aka the Pink Floyd bible) by Barry Miles (1980) Anderson and Council are still described as Georgia blues-men who were in Syd's record collection. It may come as blasphemy for vintage Floyd fans but demi-god Syd Barrett actually made an error as these two musicians stayed in the Carolinas for most of their lives. Nicholas Schaffner (1991) managed to add the years of birth and death of these obscure blues musicians, but also Mike Watkinson and Pete Anderson in their Crazy Diamond biography state that Syd 'had a couple of records by two grizzled Georgia blues-men'. Same for the lavishly illustrated, but for the rest forgettable, Learning To Fly biography by Chris Welch (1994) and a few other publications...

In 1988 though, in the first release of Days in the Life, Jonathon Green quotes Peter Jenner:

The name came from a sleeve note which one of them had read, which referred to Pink somebody or other, and Floyd somebody or other, two old blues guys, and they just thought that 'The Pink Floyd' was a nice combination, and they called it the Pink Floyd Sound.

Information doesn't always gets transferred through the appropriate channels and the booklet of the Crazy Diamond CD-box, that appeared 8 years later, still alleged that:

Barrett, Waters, Wright, and Mason reconvened as The Pink Floyd Sound, a name Syd had coined from an album by Georgia blues musicians Pink Anderson and Floyd Council.

(Barrett's record company and/or management have a history of making silly mistakes, see Dark Blog or Cut the Cake.)

All it needed to straight things out was to go to a local library (this was pre-WWW-days, remember) and look up these names in a blues encyclopedia, like yours truly did, a very long time ago. Kiloh Smith's adagio that 'Syd Barrett fans are, basically, really, really lazy people unless it comes to fighting amongst themselves on some message board' can also be expanded to rock journalists.

Pink Anderson

Although never of the grandeur of B.B. King or Muddy Waters Pink Anderson isn’t really that obscure and the perfect example for someone who likes to brag about his (or her) Piedmont blues knowledge.

Pink Anderson was born in Lawrence, South Carolina, in February 1900, and was raised in Spartanburg where he would stay his entire life. He first went on the road at age fourteen, employed by Dr. Kerr of the Indian Remedy Company, singing and dancing medicine show tunes. When the show was not travelling between Virginia and southern Georgia, with occasional trips into Alabama and Tennessee, Pink was working as a handyman in the Spartanburg storehouse where W.R. Kerr kept his trucks and stage equipment. He would stay with the troupe until Dr. Kerr retired in 1945 and never considered himself a blues singer, but a medicine show entertainer.

In 1916 Pink met Simmie Dooley, a blind blues street-singer, living in the same town. When Pink wasn’t out selling magic potions, he and Simmie played at picnics and parties in small towns around Spartanburg. They cut a few singles together in April 1928, but Anderson refused to record without Dooley (until Simmie was too old to perform). In February 1950 he was recorded by singer, folklorist and music-archivist Paul Clayton, but the tapes wouldn't be released for another decade.

Samuel Charters

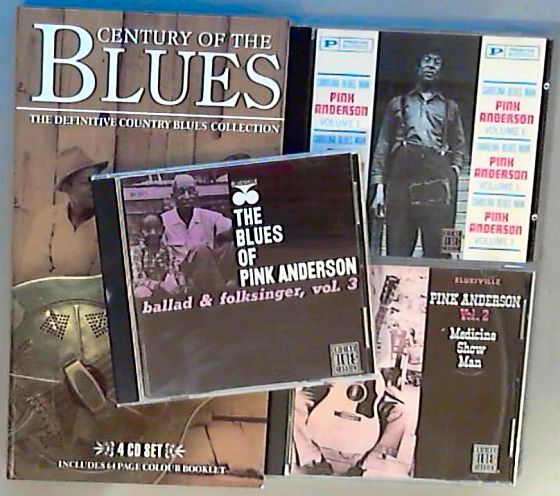

There was a kind of Pink Anderson revival in the early sixties, when he was tracked down by blues historian Samuel Charters who recorded him and brought out three albums spanning Pink's career as a Carolina blues man (volume 1), a medicine show entertainer (volume 2) and a ballad & folksinger (volume 3), otherwise Pink Anderson would've stayed a mere footnote in blues history, just like his tutor Simmie Dooley. These three albums still sell today, obviously aided by the Floydian connection, and they are of an excellent 'vintage folk & blues' quality. (Samuel Charters passed away in March 2015, aged 85: obituary.)

It is not unimaginable that some people in the Cambridge blues & beatnik circles were aware of these compilations, although they must have been rare. Floyd Council's name, however, can't be found on any of these records. Anderson's repertoire contained several Blind Boy Fuller songs, but they never met. Anderson died in Spartanburg in 1974, perhaps unaware of the fact that one of the greatest shows on earth was named after him.

Floyd Council

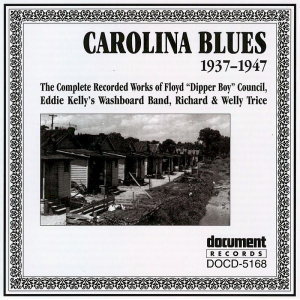

Floyd Council is a slightly different matter. Blues scholars and historians know him as a side-man on about a dozen of Blind Boy Fuller records and he only became a kind of celebrity because of the Floyd segment. His solo songs have been included on several blues compilations, because of the Pink Floyd link alone, for instance on the Century of the Blues 4-CD set (see picture above) where he comes up, right after... Pink Anderson.

Floyd Council was born in Chapel Hill, North Carolina in September 1911 and began working with legendary blues artist Blind Boy Fuller in the 1930’s. Though he is mainly known for backing Fuller, he also worked with Sonny Terry and cut some solo tracks as well. A few sources tell he may have recorded enough tracks for three albums, but only six of those have survived. The well-informed Wirz blues discography only found one lost 1937 two-tracks session.

In a (fruitless) effort to become famous he gigged and recorded as 'Dipper Boy Council', bearing the epitheton ornans 'Blind Boy Fuller's Buddy' (1937). According to the New Dictionary of American Slang, edited by Robert L. Chapman (1986), dipper refers to dippermouth, a person with a large mouth. The term showed up in Dippermouth Blues, recorded by King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band in 1923 with a 21-years old Louis Armstrong in the band, whose nickname happened to be just that, for obvious reasons.

Devil in disguise

Another stage name for Council was the 'Devil's Daddy-in-Law' (1938), probably to cash in on the popularity of Peetie Wheatstraw who was known as the 'Devil’s Son-in-Law' and whose songs often referred to the hoodoo tradition, root doctor and crossroads legends in blues.

"If black music is the father of rock, voodoo is its grandfather" write Baigent and Leigh in their overview of the occult through the ages. It is not known if Council was a follower of Vodu, but like most Negroes he must have been aware of the pagan undercurrent in his society, that was politically, culturally and socially segregated from the white highbrow class.

Probably his nicknames had been chosen by his white and highbrow class manager J.B. Long, a Maecenas for some and a thief for others, who also had Blind Boy Fuller in his stable and who employed Floyd Council on a farm he owned.

Floyd passed away in Chapel Hill, North Carolina on May 9, 1976. He is buried in an unmarked grave somewhere at White Oak A.M.E. Zion Cemetery of Sanford.

Carolina Blues

The first widely available Floyd Council compilation Carolina Blues (1936-1950) was released in 1987, a tad too late to influence Syd Barrett in his search for a name for his band. Let it be clear that in the early sixties it was close to impossible, for a Cambridge youngster, to find a Floyd Council record in the UK, unless you happened to be a very lucky and rich 78-RPM gramophone collector. We seriously doubt that anyone would lend any of these singles to a bunch of teenagers who would scratch the surfaces on their Dansette portable record players.

So that is why it was impossible for Syd Barrett to have a Floyd Council record in his collection, as some biographers have written.

Pre-War Blues

Little by little the Pink Floyd biographies had to alter the story, but it lasted until 2005 before Bryan Sinclair asked the following question to a Yahoo group of pre-war blues collectors:

Date: Mon, 14 Mar 2005 08:58:47 -0500

To: pre-war-blues@yahoogroups.com

From: Bryan Sinclair

Subject: Pink Anderson / Floyd Council

I am interested in some background info on the origin of the band name "Pink Floyd." It is my understanding that Syd Barrett came up with this hybrid by combining the first names of Carolina bluesmen Pink Anderson and Floyd Council. Bastin provides ample info with respect to dates and locales for both, but how did the two names become associated with one another, at least in the mind of Barrett?

Bryan Sinclair

Asheville, NC

It took less than a day before Bryan Sinclair has an answer. David Moore from Bristol remembered the names from a record he had in his collection:

To: <pre-war-blues@yahoogroups.com>

Date: Mon, 14 Mar 2005 15:47:51 -0000

From: "Dave Moore"

Subject: Re: [pre-war-blues] Pink Anderson / Floyd Council

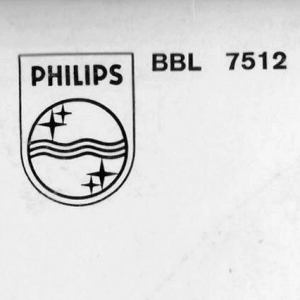

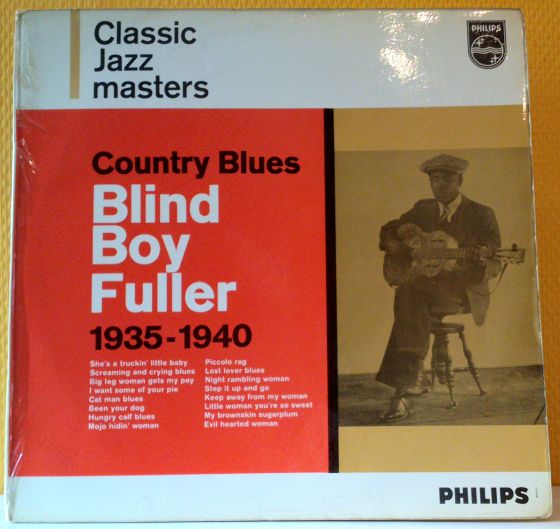

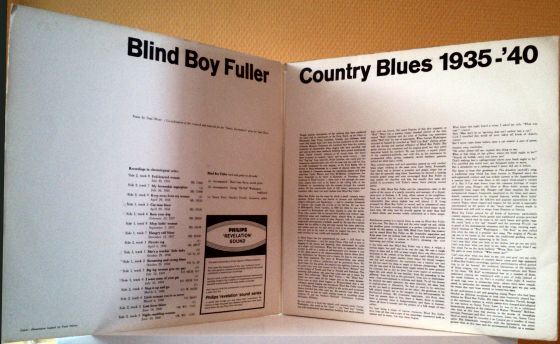

From an LP apparently in the possession of Syd Barrett: Blind Boy Fuller, Country Blues 1935-1940, issued on Philips BBL-7512, c. 1962. The sleeve notes were by Paul Oliver, and include the following:

"Curley Weaver and Fred McMullen, Georgia-born but more frequently to be found in Kentucky or Tennessee, Pink Anderson or Floyd Council -- these were a few amongst the many blues singers that were to be heard in the rolling hills of the Piedmont, or meandering with the streams through the wooded valleys."

Dave Moore

Bristol, UK

Enigma

So there we have it. All it took to find the answer was, oddly enough, to ask someone who knew, a thing nobody had ever thought of doing for 35 years. All we needed to do, was to keep on talking.

The rest is history and has been repeated in decent Pink Floyd biographies ever since. So it is a crying shame that Floyd über-geek Glenn Povey, in his encyclopedic study Echoes from 2007 still writes:

It [Pink Floyd] is the amalgamation of the first names of two old Carolina bluesmen whose work was very familiar to him [Syd Barrett].

Not... a... fucking... chance.

Update July 2017:...and yet, official Pink Floyd sources still don't grasp this. The 2017 catalogue for the Pink Floyd Their Mortal remains exhibition states at page 82 that the band was - and we quote - 'named after two of Syd Barrett's favourite blues artists'.

Blind Boy Fuller

Fulton Allen was born in July 1907 in Wadesboro, North-Carolina and learned to play the blues from the people around him. In his mid-teens he started to lose his eyesight from a maltreated disease at birth and not from washing his face with poisoned water, given to him by a jealous woman, as has been put forward by Paul Oliver.

What was a hobby at first, now became his trade, because blind Negroes didn't have many job opportunities in the thirties. Allen started busking in the streets of Durham and playing gigs with Floyd Council (aka Dipper Boy Council), Saunders Terrell (aka Sonny Terry) , George Washington (aka Bull City Red) and Reverend Gary Davis.

In 1935 he was discovered by record store owner and music promoter James Baxter Long who became manager of the lot. Re-baptised as Blind Boy Fuller he was paid about 200$ per 12 song session, not a bad deal in those days, unless you would suddenly start selling hundreds of thousands of records. And that was exactly what happened.

In five years time Blind Boy cut 139 sides, in 11 sessions taking approximately 24 days, but there would be no royalties going Fuller's way. Long would later explain that, as a rookie, he didn't understand the concept of copyrights. It is true that before 1938 Fuller's records were not credited to any author, thus (theoretically) flushing a lot of money down the drain. After April 1938 Long started putting his own name on the copyright papers when he noted down Fuller's lyrics, claiming he did this innocently and with no intent to rip Fuller.

Opinions about J.B. Long differ. As a patron of the arts he provided housing and jobs for his artists, but of course that was also a way to have them chained for life to his agency. Gary Davis and Blind Boy Fuller called him a thief, although Sonny Terry was slightly more diplomatic:

In the beginning he took all the money, but we didn't care because it started our careers.

Brownie McGhee, however, never had a bad thing to say about his manager.

The Decca Tapes

Blind Boy Fuller once tried to moonlight at Decca, but these records were rapidly pulled from the market after a complaint from his manager, who wasn't apparently such an innocent rookie after all when somebody tried to grab his artists.

James Baxter maintained he constantly provided Fuller with money, clothes, food, fuel 'and other necessities' but the singer and his wife applied several times for welfare, neglecting to mention that they already had an income from recording sessions.

The blind aid bureaucracy didn't realise that Fulton Allen and Blind Boy Fuller were the same person and they gave him a monthly allowance. Unfortunately Fuller gave his secret away when he complained to social services that his manager was not giving him the royalties he was entitled to, but the only advice they could give him was to wait until the contract ended and not to sign another one.

By 1939, suffering from alcohol related stomach ulcers, kidney troubles and probably a touch of syphilis, Fuller impatiently waited to be released from his contract and from jail, as he had shot his wife in the leg, quite an accomplishment for a blind man and a sign that he had more than money problems alone.

The Last Session

J.B. Long had the last laugh when he told Blind Boy Fuller he was still under contract with the American Recording Company. Ironically it was James Baxter who drove Blind Boy, Sonny Terry, Bull City Red and the Reverend Gary Davis to Memphis for another recording session. This time Fuller only received part of his session money, because he was already greatly in debt with his ex-manager. On top of that the Blind Assistance administration had finally found out that Fulton Allen was the same man as Blind Boy Fuller. From his ex-manager they learned that he earned about three times as much as the average household, which was still ridiculously low given the records he sold. They (logically) terminated the welfare checks.

The problem was that Fulton didn't spread his session money over several months but that it would be invariably gone by the next. James Baxter Long proposed to give Fuller a monthly salary instead of a session lump-sum, and even a house rent-free, but a stubborn Blind Boy refused, perhaps because it would have meant giving his freedom away and signing a new contract with the music promoter.

For reasons that have never been properly disclosed, but it might have been a rough life of sex and drugs and rural blues, Fulton Allen's health rapidly declined and he died in February 1941, at only 33 years of age.

Classic Jazz Masters

In his book 'How Britain Got The Blues', R.F. Schwartz notes that:

...most critics agreed that the great blues of the past would never be reissued [in the fifties, FA], but some collectors were committed to making this repertoire accessible.

For the smart understander: illegally. History repeats itself, ad infinitum.

At first many jazz and blues reissues were bootlegs, made by collectors for collectors and taken from the original 78-RPM records. As the musicians had been paid flat fees anyway, and seldom received royalties, no harm was done, although the record labels obviously had different opinions.

With a growing demand for vintage blues the major labels finally

understood that there was a market and that the costs for producing

these albums was minimal. Philips began its Classic Jazz Masters

Series in 1962 with:

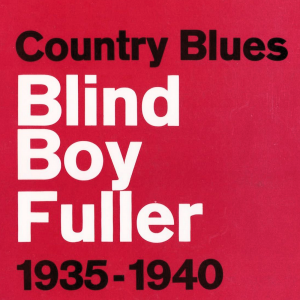

Blind Boy Fuller 1935-1940 Country Blues

(BBL-7512),

Bessie

Smith 1923-1924 Bessie's Blues (BBL-7513),

followed by:

Robert

Johnson 1936-37 (BBL-7539).

That last one was almost immediately deleted for legal reasons (apparently even record companies have difficulties sorting copyrights out) but so many copies had already been sold to blues-hungry teenagers that a whole generation was inspired to start their own bands. British blues boom was a fact.

On his first trip to England, in November 1962, Bob Dylan bought two albums he brought back to the States. The first one was Blues Fell This Morning, a Southern Blues compilation, that accompanied Paul Oliver's book with the same name. The second was the Philips Blind Boy Fuller Country Blues album. (A picture of that album, with Bob Dylan's signature, can be found on Recordmecca: Bob Dylan's Muse: Suze Rotolo, 1943-2011.)

Blues was a tidal wave that couldn't be stopped. 1965 saw a British tour of Reverend Gary Davis and his old mates Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry headlined the Cambridge Folk Festival on the 31st of July.

Blues In Cambridge

That the blues was also popular in Cambridge was proved by bands as The Hollerin' Blues, named after the 1929 Charley Patton song, Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues. Incidentally, Blind Boy Fuller's Piccolo Rag, that is present on the 1962 Country Blues compilation, has the lyrics:

Said, when I'm on the corner hollerin'.

"Whoa! Haw! Gee!"

My gal's uptown hollerin'.

"Who wants me?"

As their only way of communication, slaves or black farm workers would holler to each other across the fields. Sometimes these hollers would be wordless, sometimes they would form sentences and grow into songs that were sung in call and response. Spirituals, work songs and hollers influenced and structured early blues.

Back To The Bone

The line-up of this 1962/63 rhythm & blues band was Barney Barnes (piano, harmonica and vocals), Alan Sizer (guitar), Pete Glass (harmonica) and Stephen Pyle (drums). Rado 'Bob' Klose and Syd Barrett joined them at least once at the Dolphin Club in Coronation Street, but he was never a band member. According to Gian Palacios Barrett also sat in on several jam sessions, mainly because he showed a certain interest in Juliet Mitchell who lived in the house where the band rehearsed.

Women were the reason why the band cut itself loose from their old management and they reincarnated as Those Without with Warren Dosanjh as their new manager. (See also Antonio Jesús interview: Warren Dosanjh, Syd Barrett's first manager.) Stephen Pyle remembers in The Music Scene Of 1960s Cambridge that he actually suggested Pink Floyd as the band's new name, but this was rejected by the others.

Which one's Pink?

It means that the Philips Blind Boy Fuller Country Blues album was well known by the Hollerin' Blues mob, including Syd Barrett, who joined Those Without for about a dozen of of gigs. It could also mean that the Pink Floyd name, contrary to general belief, was not thought up by Syd and that it might have been an incidental joke. Over the last few years though, Stephen Pyle changed this story a bit, claiming that he and Syd used to invent band names all the time, just for fun. 'Pink Floyd' as such never was a contestant to rename The Hollerin' Blues. Not that it really matters, but we asked Stephen Pyle anyway:

I am afraid time has taken is toll on my memory.

But Syd and I used to invent band names when Those Without were already in existence, as to who's album it was I think it was mine.

It was Dave Gilmour who claimed that I was the source, and he must have got that from Syd.

Country Blues: a review

The 1962 Philips album Country Blues, Blind Boy Fuller 1935-1940 is a wayward compilation, containing 16 tracks, ranging from the obvious to the less than obvious. It contains tracks from 10 different sessions, recorded over 12 days, starting with the first session that made Fuller a star and ending with the last one he would ever do. Intriguingly - for Pink Floyd anoraks - is that none of the tracks have Floyd Council on them, but George Washington (aka Bull City Red) and Sonny Terry can be found on several songs. So the record that gave the Pink Floyd name away actually doesn't have Pink Anderson, nor Floyd Council on it.

Why don't you listen to the Country Blues album while reading this review?

A Spotify playlist (login needed) for the same album can be found here: Country Blues. Throughout the review many YouTube and Wikipedia links will be given, checking them out will take many hours of your life. A Blind Boy Fuller gallery with hi-res images of the record, its cover and the liner notes has been uploaded: Blind Boy Fuller.

Country Blues Side One

She's A Truckin' Little Baby

The album starts with She's A Truckin' Little Baby, a country dance tune and a song that has many incarnations. Big Bill Broonzy recorded it as Trucking Little Woman, John Hammond Jr. as Trucking Little Boy and John Jackson as Trucking Little Baby. All have different lyrics, but they're essentially the same song. Led Zeppelin sometimes included the song as Trucking Little Mama in their R&B medley during Whole Lotta Love.

Blind Boy Fuller is generally cited as the originator of the terms 'keep on truckin' (in Truckin' My Blues Away, not on this compilation) and 'get your yas yas out' (not included either). Several of his songs belong to the hokum genre - humoristic blues with double entendres and sexual innuendos – or bawdy blues. His What’s That Smell Like Fish, Mama (not included) as being one of the most risqué ever.

There's a bit of playful innuendo in Truckin' Little Baby with the line:

she got good jelly

but she's stingy with me.

Jelly is a culinary metaphor for female attractiveness and/or sexuality. Imagine this tune with an electric guitar, add some bass and a drum and there you have it: rock'n roll.

Recorded: October 29, 1938, with Bull City Red (George Washington) on

washboard.

Sound

& Lyrics

Source(s):

Lyr

Req: Trucking Little Baby / ...Woman / ...Mama

Screaming And Crying Blues

Screaming And Crying Blues can't get more 'default' as it is about a man, waking up in the morning and realising his woman has left him. The term comes back in different songs, one of them Screamin' and Cryin' by Muddy Waters (1949) and one by Morris Pejoe (1956).

I was worried and grieving,

about that girl had done left me behind.

Recorded: October 29, 1938.

Sound

& Lyrics

Big Leg Woman Gets My Pay

Big legged women are something of a tradition in blues and, once again, have been cited in a Led Zeppelin song (Black Dog) where it is said that:

a big-legged woman ain't got no soul.

And that might be quite an insurmountable problem for a band that has been flirting with Satanist tendencies. Mississippi John Hurt recorded Big Leg Blues in 1928, Roosevelt Sykes had Big Legs Ida Blues in 1933, Kokomo Arnold Big Leg Mama in 1935, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry covered Bill Gaither's Another Big Leg Woman as Big-Legged Woman and so on...

A big legged woman is just another way of saying that she is sexually attractive and with 'gets my pay' Fuller is implying he wants to give her more than his monthly salary alone, but you probably already had figured that out.

Recorded: July 12, 1939, with Bull City Red (George Washington) on

washboard.

Sound,

but no Lyrics found.

Source(s): A

big legged woman ain't got no soul

I Want Some Of Your Pie

I Want Some Of Your Pie obviously is an example of a risqué blues, without really being too smutty, unless we semantically dig deeper. Officially the song goes like this:

Says, I'm not jokin' an' I'm gonna tell you no lie,

I want to eat your custard pie.

But most hear something else:

Says, I'm not jokin' an' I'm gonna tell you no lie,

I want to eat your custy pie.

In a mighty interesting online essay that has unfortunately disappeared from the web at the end of 2014 'The use of food as a sexual metaphor in the blues' (Elise Israd) it is suggested that the use of code words for romantic and sexual activity may have come out of fear and oppression. Plantation owners were not amused that their (male) slaves would discuss sex in public and thus they used innocent synonyms for the yummy things they wanted to describe.

When it came to producing and selling blues records there was as well the matter of censorship. As often in these cases the record companies had a double standard, calling the naughty bits by their proper name was considered obscene and legally forbidden, but they didn't see any harm in selling songs about sugar plums, fish and custy, custard, crusty or cushdy pies.

I Want Some Of Your Pie (1939) is one of those songs that has different incarnations. It can be found as Custard Pie (1947) by Sonny Terry and as Custard Pie Blues (1962) by Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. Buddy Moss and Pinewood Tom recorded an early version, with slightly other lyrics, as You Got To Give Me Some Of It in 1935, 4 years before Blind Boy Fuller.

It might not come to you as a surprise that Led Zeppelin's 1975 album Physical Graffiti starts with a track called Custard Pie, what made one fan seriously wonder if Sonny Terry covered it retroactively from the dark angel that is Robert Plant.

Recorded: July 12, 1939, with Sonny Terry (harmonica) & Bull City Red

(washboard).

Sound

and Lyrics

Source(s):

Custard

Pie

Cat Man Blues

The next three songs all have an animal theme and in these cases animals are used as an allegory for a situation man is not really happy with.

Cat Man Blues is the story of a man who returns home, hears a noise in another room and is told by his wife it is nothing but the cat.

Went home last night, heard a noise,

I asked my wife what was that?

Said man don't be so suspicious,

that ain't nothin' but a cat.

Lord I travelled this world all over mama,

takin' all kinds of chance.

But I never come home before,

seein' a cat wearin' a pair of pants!

While the words are funny, the situation isn't and the protagonist surely doesn't appreciate that the cat man is stealing his cream away.

Recorded: April 29, 1936, (recorded twice that day, actually).

Sound

(take1), Sound

(take 2) and Lyrics

Been Your Dog

Been Your Dog has a man complaining how badly treated he is by his wife. In Untrue Blues, not on this record, Fuller describes it as follows:

Now you doggin' me mama, ain't did a thing to you.

And you keep on doggin' no telling what I'll do.

Now you dog me every morning,

give me the devil late at night.

Just the way you doggin' me,

I ain't goin' treat you right.

Been Your Dog plays with the same subject:

I've been your dog mama

ever since I've been your man...

Fuller complains how he has to work hard all day, only to come and find a drunk wife in bed and ponders if he should leave her and make room for another man.

Recorded: February 10, 1937.

Sound,

but no Lyrics found.

Hungry Calf Blues

Hungry Calf Blues is much more funny and risqué, although it has again the undertone of a man who is cheated on and who does his best to win his woman back. The song, so tell the experts, is a variation of Milk Cow Blues by Sleepy John Estes (1930) although the lyrics haven't got much in common. In 1934 Kokomo Arnold covered the song, still much the same as the original one.

Fuller's version is closer to Milkcow's Calf Blues, recorded by Robert Johnson on his last session in June 1937 and with a new set of lyrics. Copyright wasn't really an issue in those days, as Lawrence W. Levine explains in his study 'Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom'.

Black singers felt absolutely free to take blues sung by others - friends, professional performers, singers on records - and alter them in any way they liked.

Fuller certainly was no exception to that rule and re-utilises a couple of Johnson's lyrics:

Your calf is hungry mama, I believe he needs a suck.

and

Your milk is turnin' blue, I believe he's out of luck.

, but then he is off into his own miserable territory:

I found out now mama,

the reason why I can't satisfy you... (…)

You've got a new cat,

he's sixteen years old.

There's that trousered cat again! From then on the song turns pseudo-autobiographical and the protagonist promises he will be faithful to his wife from now on and to treat her well:

I'm gonna save my jelly, mama,

gonna bring it right home to you. (...)

You can't find no young cat,

roll jelly like this old one do.

For those thinking that Fuller is keen on sweet desserts, we would like to add that jelly is not what you think it is, except when you have a perverted mind and then it is exactly what you think it is.

A stanza later we learn that the I-person in the song is none other than Fuller himself. He apologises that the flesh is weak and the blues groupies abundant:

Says I got a new way of rollin' mama,

I think it must be best.

Said these here North Carolina women

just won't let Blind Boy Fuller rest.

But just when you think it would be wise to show some discretion male chauvinist ego takes over again and Fuller brags that he is the best lover around:

Said I got the kind of lovin',

yes Lord, I think it must be best.

Said I roll jelly in the mornin'

and I also roll at night.

I said hey hey, I also roll at night.

And I don't stop rollin',

till I know I rolled that jelly just right.

We doubt the lyrics need further explanation, unless perhaps you are confused by the terms jelly and jelly-roll, another example of pastry being used as a sexual metaphor. Harry's Blues gives a neat definition and lists 15 songs that use the same terminology.

Recorded: September 9, 1937.

Sound

and Lyrics

Source(s):

Milk

Cow Blues

Mojo Hidin' Woman

The last song on side A of the album is Mojo Hidin' Woman, and compared to the previous lot a rather solemn and respectful one, although it still blames the wife who brings misery over the man. Blind Boy Fuller refers (literally) to black magic and the woman's habit of concealing a mojo, a magical charm bag, on her body.

Fuller probably means a 'nation sack', a term originating from the Memphis area, which is a red flannel bag containing roots, magical stones and personal objects, worn by a woman, meant to keep her man faithful and make him generous in money matters.

Other sources say it should be 'nature sack'. Harry Middleton Hyatt, a white Anglican minister who studied folklore in the thirties and who documented over 13000 (!) magic spells and beliefs, may have misunderstood the Negro term 'naycha' and wrote it down as 'nation' instead of 'nature'. In hoodoo it was seriously believed that the magical bag controls a man's 'naycha' or virility. No wonder that Blind Boy Fuller didn't laugh at this one.

To make the spell powerful some objects of the love interest were put in the bag, a photograph, his name or signature on a piece of paper, cloth, fingernail clippings, (pubic) hair and other intimate by-products... The bag was worn under the clothes, at the lower waist for obvious magical reasons, and it was strictly forbidden to be touched, or even seen, by a man. Married women would hide it before going to bed:

Yo' know, a man bettah not try tuh put dere han' on dat bag; yo' know, he betta not touch. He goin' have some trouble serious wit dat ole lady if he try tuh touch dat bag, 'cause when she pulls it off at night -- if she sleeps by herself, she sleeps wit it on; but if she got a husban', yo'll see her evah night go an' lock it up in dat trunk. [Taken from Nation Sack @ Lucky Mojo.]

Not that a pious man would ever try to do that, as touching the bag would make him lose, as Austin Powers erroneously put it, 'his mojo'. As the naycha sack was strict taboo for a man it was a safe place for the woman to put her belongings in, money and tobacco, and if the money had been given to her by her husband, that could only act as an extra charm.

Mojo Hidin' Woman is the same song as Stingy Mama, recorded a month earlier, but with a new title. Fuller knows exactly what he sings about:

My girl's got a mojo.

She won't let me see.

In true hokum tradition the song is full of double entendres, starting with the first line:

Stingy mama, don't be so stingy with me.

As the (secret) mojo was often used or hidden inside a purse a 'stingy' woman is one who doesn't like to spend money, but in this context mojo is of course used as an euphemism for sex. Being the sexy motherfucker he is, Fuller knows she will finally give in:

I say, hey-hey, mama, can't keep that mojo hid...

'Cause I got something, mama, just to find that mojo with.

And that's a verse Fuller lends almost literally from Blind Lemon Jefferson's Low Down Mojo Blues (1928).

The song perfectly ends with a play of words, ingeniously hinting at the 'stingy' remark of the beginning:

Mama left me something called that stingaree.

Says, I done stung my little woman

and she can't stay away from me.

Sex has never been described better, even if you don't immediately grasp the concept of a stingaree, but once again Harry's Blues comes to the rescue. This is, if you ask the Reverend, as poetical as:

'Cause we're the fishes and all we do

the move about is all we do

well, oh baby, my hairs on end about you..

Recorded: September 7, 1937 (Stingy Mama: July 12, 1937)

Sound

and Lyrics

Country Blues Side Two

Piccolo Rag

Side two starts with the Blind Boy Fuller classic Piccolo Rag that can be found on about every compilation of him. It's a joyous and irresistible ragtime guitar dancing tune that is typical of the Piedmont Blues style. It is a fun track with a direct message that doesn't need to be further explained:

Every night I come home

you got your lips painted red.

Said, "Come on Daddy and let's go to bed."

In the first decade of the twentieth century a 'daddy' in African American slang was a pimp, but later the term was generalised to any male lover.

Recorded: April 5, 1938.

Sound

and Lyrics

Lost Lover Blues

Lost Lover Blues is the sad story of a man who takes a freight train to 'a far distant land', probably to look for work, and who gets a telegram to immediately return home. On his return he finds that his lover has died while he was on his journey. The message is clear and direct with no double entendres, but this is normal as the subject is one of melancholy and sadness.

Then I went back home,

I looked on the bed

And that best old friend I had was dead

Lord, and I ain't got no lovin' baby now

Recorded, June 19, 1940 with Bull City Red (washboard).

Sound

& Lyrics

Night Rambling Woman

Fuller's last solo song recorded on the 19th of June 1940, in a 'superstar' session that also had Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Eli Jordan Webb (originally from Nashville) and Bull City Red (credited on some tracks as Oh Red). Thirteen solo tracks were recorded, 8 by Fuller and one by Sonny Terry.

The remaining four tracks are credited to a band called Brother George & His Sanctified Singers, actually an alias for all involved, singing religious inspired gospel and blues, with titles as: 'Must have been my Jesus', 'Jesus is a holy man' or 'Precious Lord'. Fuller did not sing on this gospel session and it may have been George 'Oh Red' Washington who was the main vocalist.

Rambling Woman is not an unique term as it was used in the traditional Ragged But Right that dates from around 1900. Recorded versions exist by the Blue Harmony Boys (Ragged But Right, 1929) and Riley Puckett (Ragged But Right, 1935). As a traditional it had many different lyrics including this very raunchy version:

Just called up to tell you that I'm ragged but right

A gamblin' woman ramblin' woman, drunk every night

I fix a porterhouse steak every night for my boy

That's more than an ordinary whore can afford

Country stars Riley Puckett and George Jones (I'm Ragged but I'm Right) used more innocent lyrics and changed the protagonist to a gambling man, instead of a woman. Covers by Johnny Cash (I'm Ragged but I'm Right) and Jerry Garcia (Ragged but Right) also exist.

Night Rambling Woman was posthumously issued by Brownie McGhee in 1941, partly as a tribute to his friend, but probably as a cunning plan from manager J.B. Long to cash in on Fuller's reputation by covering a previous unreleased track. J.B. Long also put the epithet 'Blind Boy Fuller #2' on early McGhee singles, for instance on the song Death Of Blind Boy Fuller.

Night Rambling Woman is another take on the infidelity of women with one line taken from Victoria Spivey's 1926 song Black Snake Blues, generally regarded as a stab at Fuller's own mortality:

My left side jumps and my flesh begin to crawl.

It has been said that Fuller was a master of eclecticism rather than the originator of a style and there are many recorded examples in which the influence of other popular blues artists can be heard.

Recorded: June 19, 1940.

Sound,

but no Lyrics found.

Source(s): Ragged

But Right

Step It Up And Go

Step It Up And Go, credited to J.B. Long, was Fuller's biggest hit, although far from an original. Known as Bottle Up And Go it was recorded in 1939 by Tommy McClennan, himself referring to Bottle It Up And Go, written by Charlie Burse for the Picanniny Jug Band in 1932. J.B. Long claimed he heard a song 'You got to touch it up and go' from an old blues man and that he re-wrote the lyrics for Fuller to sing it a couple of days later.

Blues biographer Bruce Bastin found out that just before the Fuller session Charlie Burse had cut a new version of his own song, now titled: 'Oil It Up And Go', in the same studio. That is probably where J.B. Long heard and copied it from.

Many artists recorded this song after that, and all versions are different. It seems as if every artist who performed the song, made up his own lyrics or added a verse or two. Some of the people who recorded the song are: B.B. King, Big Jeff and the Radio Playboys, Bob Dylan, Brownie McGhee, Carl Story, Harmonica Frank Floyd, John Lee Hooker, Mac Wiseman, Maddox Brothers & Rose, Mungo Jerry, Sonny Terry and The Everly Brothers.

The song is in the hokum style with casual observations about (again) the terrible treatment men suffer from their women.

Recorded: March 5, 1940, with Bull City Red (washboard).

Sound

& Lyrics

Source(s):

Bottle

Up and Go

Keep Away From My Woman

Keep Away From My Woman, this song actually exists in two different takes, from the same session, with about 20 seconds difference, but the vinyl record doesn't specify what version it is (same for Cat Man Blues, by the way). The title already gives away what the tune is about.

Recorded: April 29, 1936.

Sound

(take 1, 2:54), Sound

(take 2, 3:14), but no Lyrics found.

Little Woman You're So Sweet

Little Woman You're So Sweet is a love song, a small masterpiece, where Fuller actually mentions himself.

Hey mama, hey gal,

don't you hear Blind Boy Fuller callin' you?

You're so sweet, so sweet, yeah sweet,

my little woman, so sweet...

The song was first recorded as So sweet, so sweet by Josh White in 1932 and Fuller's version is nearly a carbon copy of the original.

“The effects of the phonograph upon black folk-song are not easily summed up.”, writes Lawrence Levine in 'Black Culture and Black Conciousness'. Mamie Smith's second single Crazy Blues (1920), the first vocal blues recording in history, had sold over one million copies despite being exorbitantly priced at one dollar. In the mid twenties five to six million blues records were sold per year, almost exclusively to the black public, who were with about 15 million in the USA. After the blast-off with mostly female singers talent scouts roamed the states to audition regional bluesmen who brought their version of traditional blues to the rest of the land.

It can't be denied that the booming record sales had a disruptive effect on many local folk styles and traditions, but on the other hand, the thousands of 78-RPM records archived songs that would otherwise have been lost for ever. Even if the records had to fit inside the three minutes format, blues had no beginning and no end, as the one performer took up where the other left off and singers were constantly referring to each other. A blues song didn't belong to the singer, it belonged to the people.

Other trivia: Blues band Shakey Vick named their first album, in 1969, after this song.

Recorded: March 6, 1940.

Sound

& Lyrics

Brownskin Sugar Plum

Brownskin and Sugar Plum are terms that regularly appear in blues songs, although the combination of both might be unique to this one.

It has been a while since we mentioned Led Zeppelin but their Travelling Riverside Blues, itself named after a Robert Johnson tune (Traveling Riverside Blues), ends by mentioning this Fuller song. Another fine example of hokum blues, the lyrics are just damn' horny:

Oh just tell me mama

Where do you get your sugar from

Aw just tell me sugar

where you get your sugar from

I believe I bit down

On your daddy's sugar plum

Recorded: July 26, 1935.

Sound

& Lyrics

Evil Hearted Woman

The last song Evil Hearted Woman is one where the female race is again described at its worst. It isn't the only time Fuller sings about an evil hearted woman as the term is also used in his Untrue Blues (not on this compilation).

Recorded: July 25, 1935.

Sound,

but no Lyrics found.

Conclusion

Paul Oliver (on the Country Blues liner notes):

In Evil Hearted Woman, My brownskin sugarplum, and Keep away from my woman there is love, there is desire, there is menace, there is jealousy, there is disappointment and there is humour.

We couldn't have said it better. If this record was good enough for Syd Barrett to listen to, it surely is good enough for us as well. Listening to Country Blues may be a challenge if your ears have been used to the electric and electronic sounds of the third millennium, but this is R&B in its embryonical stage. Dig it.

Epilogue

The Holy Church of Iggy the Inuit started in 2008, more as a prank than anything else (see: Felix Atagong: an honest man), and has worn out its welcome more than once. Feeling that our expiration date was reached at least a year ago, it is time to say goodbye. And what better opportunity than to do it with the album that named the best band in the word.

Let's give our final words to one of our esteemed colleagues, the Reverend Gary Davis:

One of these days about 12 o'clock

This old world's gonna reel and rock

I belong to the band

Hallelujah

(I Belong to the Band, Hallelujah, 1960)

Many thanks to: Bennymix, Cagey, Caitrin, Deanna, Jim Dixon, Dorothea,

Brian Hoskin, Elise Israd, Mudcat.org,

Parla, Stephen Pyle, Tony Russell, Sorcha, Stagg'O'Lee, Dave T,

Winifred, Wordreference.com,

Zowieso...

♥

Iggy ♥ Libby ♥ friends, lovers and fans...

Sources (other than the above mentioned links):

Baigent,

Michael & Leigh, Richard: The Elixir and the Stone, Penguin,

London, 1998, p. 399.

Bastin, Bruce: Blind Boy Fuller,

biography in: Stefan Grossman's early masters of American blues guitar:

Blind Boy Fuller, Alfred Music Publishing, 2007.

Bastin, Bruce: Red

River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast, University of

Illinois Press, 1995, p. 223-234.

Blake, Mark: Pigs Might Fly,

Aurum Press Limited, London, 2007, p. 43.

Charters, Samuel: Carolina

Blues Man, Pink Anderson vol. 1 record liner notes, 1961.

Charters,

Samuel: Medicine Show Man, Pink Anderson vol. 2 record liner

notes, 1961.

Charters, Samuel: Ballad & Folksinger, Pink

Anderson vol. 3 record liner notes, 1961.

Dosanjh, Warren: The

music scene of 1960s Cambridge, I Spy In Cambridge, Cambridge, 2013,

p. 54.

Goodall, Howard: Painters, Pipers, Prisoners. The musical

legacy of Pink Floyd., in: Pink Floyd. Their Mortal Remains, London,

2017, p.82.

Green, Jonathon: Days In The Life, Pimlico,

London, 1998, p. 104.

Hogg, Brian: What Colour is Sound?,

Crazy Diamond CD box booklet, 1993.

Israd, Elise: The use of food

as a sexual metaphor in the blues, 2008?, (original page

deleted, partially archived

page)

Levine, Lawrence W. : Black Culture and Black Consciousness:

Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom, Oxford

University Press, 2007 reprint, p. 225-232.

McInnis, Mike : This

one's Pink, Unraveling the mysteries behind the Pink Floyd name,

2006.

Miles, Barry: London Calling: a countercultural history of

London since 1945, Atlantic Books, London, 2010, p. 181.

Miles,

Barry: Pink Floyd The Early Years, Omnibus Press, London, 2006,

p. 46.

Miles, Barry & Mabbett, Andy: Pink Floyd The Visual

Documentary, Omnibus Press, London, 1994 edition, unnumbered pages,

1965 section.

Obrecht, Jas: Blind

Boy Fuller: His Life, Recording Sessions, and Welfare Records, 2011.

Oliver,

Paul: Country Blues 1935-'40, Blind Boy Fuller liner notes, 1962.

Palacios,

Julian: Lost In The Woods, Boxtree, London, 1998, p. 40.

Povey,

Glenn: Echoes, the complete history of Pink Floyd, 3C Publishing,

2008, p. 18.

Pyle, Stephen: Pink & Floyd, message on

21/03/2015 16:38.

Schaffner, Nicholas: Saucerful of Secrets,

Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1991, p. 30.

Schwartz, Roberta Freund

: How Britain Got the Blues: The Transmission and Reception of

American Blues Style in the United Kingdom, Ashgate Popular and Folk

Music Series, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008, p. 91-95.

Stagg'O'Lee: Blind

Boy Fuller, Sa Vie, Gazette Greenwood, 2003.

Watkinson, Mike &

Anderson, Pete: Crazy Diamond, Omnibus Press, London, 1993, p. 31.

Weck,

Lars: Pink Floyd på visit, Dagens Nyheter, 1967-09-11.

Welch,

Chris: Learning to Fly, Castle Communications, Chessington, 1994,

p. 26.

Zolten, Jerry: Great God A'Mighty! The Dixie Hummingbirds :

Celebrating the Rise of Soul, Oxford University Press, 2002, p.

54-57.

Discography:

Pink

Anderson

Floyd

Council

Blind

Boy Fuller

So long, and thanks for all the fish.