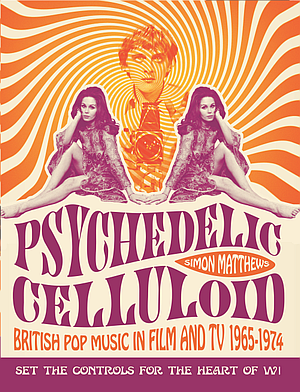

Psychedelic Celluloid

This article started as a review of Psychedelic Celluloid by Simon Matthews but ended up as a long-read about Pink Floyd at the movies. Sorry, I can't help it. (This article does not pretend to describe all Pink Floyd related movies.)

Contents: • Psychedelic Celluloid • The Big Boss • Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan • More Sound Delinquents • Psychedelic Celluloid (reprise) • À Coeur Joie • The Touchables • The Committee • The Magic Christian • More • The Body • Entertaining Mr. Sloane • La Vallée • Psychedelic Celluloid (listomania) • Salome • Psychedelic Celluloid (conclusion) • La Marge • Kindle rant •

Psychedelic Celluloid

I got a mail, a couple of months ago, from Simon Matthews, saying that he was working on a book that would explore the interaction between (psychedelic) pop music and British movies, in the golden era that was Swinging London. Not really coming as a surprise he added that Pink Floyd would figure in it a couple of times. I made a mental note to check it out, but like so many things it got lost in the dark corners of my soul. Call it divine intervention, or just a case of serendipity, but when Brain Damage did a short write-up of the publication it all came back to me and ten minutes later my Kindle was purring with joy.

Matthews starts his book by mentioning George Melly’s Revolt Into Style, a collection of sixties essays that has been borrowed from in all self-respecting Swinging London books in the past forty years. His introduction ends with the ad-hoc announcement that the most prominent ‘movie’ music performers between 1965 and '74 were not The Beatles, nor The Rolling Stones, but, yes, you’ve already guessed it: (The) Pink Floyd.

During my four decades long love/hate relationship with the band I have trodden many paths, some narrower than others, and so it may not come as a surprise to you that I have also tried to acquire some information on the lads in movieland. We all know that several members of the Cambridge mafia, revolving around the band, were dabbling into film: Nigel Lesmoir-Gordon, Mick Rock, Anthony Stern, Storm Thorgerson to name just a few.

It happily surprised me that, in the chapter ‘Set the Controls for the Heart of W1!’, Matthews is casually mentioning that the Floyd’s music can also be found on two kung fu flicks: ‘Fist of Fury’ and ‘Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan’. I am familiar with those as well as my quest into Floyd in filmland has brought me to the weirdest places. Did you know there is a Syd Barrett presence in a Freddy Mandingo movie? Well, let me tell you, you really don't want to know.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

A fistful of Floyd

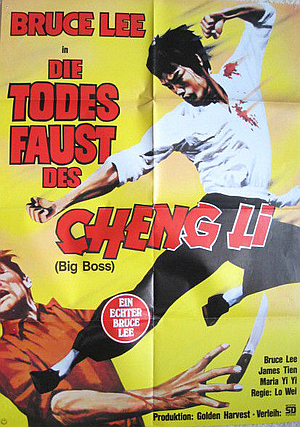

唐山大兄 Tang Shan Da Xiong (The Big Boss) is a (fairly stupid) 1971 Hong Kong movie that put a fairly unknown martial artist into the spotlight. Bruce Lee plays a somewhat dorky fellow, revenging the murders on his relatives, who found out the local ice factory is being used for drugs smuggling.

When the movie arrived in an American version it was retitled as Fists Of Fury, creating a mess for generations to come as there would be another Bruce Lee movie the next year called Fist Of Fury (without the s). Perhaps it was the other way round, as even Wikipedia isn't really sure which is which (and neither does Simon Matthews). Most of the world calls the movie The Big Boss, except for Germany, who like to give the plot away and baptised it Die Todesfaust des Cheng Li (The deadly fist of Cheng Li).

Not only the title gives food for confusion. The movie has been issued in half a dozen of different versions with entirely different soundtracks.

A first music score was composed by Wang Fu-ling for the (original) Mandarin release. It is believed Cheng Yung-yo assisted with that soundtrack, although uncredited. This movie was horribly dubbed into English for a limited run in the Anglo-Saxon world.

A second soundtrack was made by German composer Peter Thomas when the movie was re-cut and re-dubbed for the international market. This 1973 westernised version had several erotic and gory scenes deleted, including the legendary scene where Bruce Lee cuts an adversary's head in two halves with a saw.

A third soundtrack, using the international cut, was arranged by Joseph Koo, for a Japanese release, probably around 1974.

A fourth soundtrack for a Cantonese release in 1983 combines the Joseph Koo score (#3) with the one of Peter Thomas (#2) and adds incidental 'stock' music. This one includes snippets from Pink Floyd and King Crimson (Larks' Tongues In Aspic, Part Two).

Cut Into Little Pieces

An overview of Pink Floyd music in The Big Boss, thanks to the Martial Arts Music Wiki, with (dead) links to the exact sequence. Contains some minor spoilers.

Obscured by Clouds (1972, Obscured by Clouds)

Cheng Chao-an

(Bruce Lee) and his cousin Hsiu are being followed by casino bouncers (13:05).

Repeated

when Hsiao Mi (the big boss), his son Chiun and some henchmen are

training (26:35).

Time (1973, The Dark Side of the Moon)

Hsiu and his brother

visit the big boss at his mansion, trying to find out why two of their

family members have disappeared (29:05).

Chen

Chao-an (Bruce Lee) is invited for a meeting with the ice factory's

manager (47:50).

Chen

Chao-an visits the big boss to find out why four of his relatives have

disappeared (01:06:14).

Time / The Grand Vizier's Garden Party (Entertainment)

(1969, Ummagumma)

Mixed together this can be heard when Hsiu and his

brother try to escape from Mi's killer squad (31:58).

As far as we know, the Floydian soundtrack was only available on a Cantonese 1983 re-release, explaining that a 1973 song anachronistically appears on a 1971 movie. It isn't certain if the Pink Floyd tracks were properly licensed as they are not mentioned on the end credits. To add insult to injury other cuts of the movie - with alternative 'hybrid' soundtracks and extra or longer scenes - have circulated, so it is all rather messy. For a (partial) comparison of the different versions: Big Boss @ Movie Censorship.

Update November 2022: a very detailed description of the different versions of the movie and its soundtracks can be found on IMDB: The Big Boss (1971) - Alternate Versions.

Bruceploitation

Bruce Lee died unexpectedly in 1973 and the posthumous documentary The Man and the Legend (original title: Li Xiao Long di Sheng yu si) contains next to the King Crimson piece that was already mentioned above, Pink Floyd's One of These Days (1971, Meddle) and On The Run (1973, The Dark Side of the Moon).

After 1973, several Bruceploitation movies were made, often with a conspiracy theme. Tian Huang Ju Xing (Exit the Dragon, Enter the Tiger) from 1976 is not different and has actor Bruce Li (real name: Ho Chung Tao) fighting his way through some shady drug deals in something that will not be remembered as a great martial arts movie. Even the soundtrack borrows completely from others and has next to Isaac Hayes and John Barry, Shine On You Crazy Diamond (1975).

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

Trouble in the brothel

A decade before The Big Boss (1983 cut) another kung fu movie had found out about the martial strength of Pink Floyd.

愛奴 Ai Nu, awkwardly renamed for the western market as Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan, is a 1972 Hong Kong movie about the 18-year old Ai Nu who is kidnapped from her family and brought to the governor's brothel.

After the default set of humiliations and punishments she apparently accepts her fate and learns the noble art of self-defence from 'madam' Chun Yi. Once a kung fu champ she uses her seductive powers to eliminate her wrongdoers, one by one.

Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan is a mixture of blood vengeance, lesbian sensualism (in covert seventies style) and it has been named as one of the inspirational landmarks for Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill. Every scene looks so artificially crisp it nearly hurts the eyes and if Walt Disney ever makes a movie set in a brothel this is certainly how it will look like. Undoubtedly a seventies classic, director Yuen Chor (Zhang Baojian) can, without doubt, be placed next to Borowczyk, Fellini or Pasolini.

Another one bites the dust

Unfortunately the original soundtrack can't really decide between traditional Chinese and Tex-Mex western style tunes. Two Pink Floyd tracks of the 1970 Zabriskie Point soundtrack are prominent in three decisive scenes. (The links given here point to a very bad copy, dubbed in English, with terrible sound.)

Come In Nr. 51 (Your Time is Up)

Ai Nu has just been tortured

by Chun Yi, who promptly falls in love with her (link).

After

the final duel, when Ai Nu kisses her dying lover goodbye (link).

Heart Beat, Pig Meat

A few seconds of Heart Beat, Pig Meat at

43 minutes when Ai Nu and her lesbian lover openly discuss the first

murder (not present on the YouTube version).

(The DVD has a

documentary about the movie that uses the Zabriskie soundtrack even

more, by the way.)

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

More Sound Delinquents

In Psychedelic Celluloid, Simon Matthews writes that Pink Floyd can be heard in two kung fu movies, but there is more, much more...

The Kung Fu Magazine forum has a 47-pages thread with, at the time of writing, 643 verified tracks (of different composers, bands and artists) that have been used, legally or illegally, in dozens of films. Sometimes the songs are used in its entirety, but often snippets of a second or less have been 'sampled' into the soundscape. Venomous Centipede at shaolinchamber36.com came up with the following impressive Pink Floyd list. All Hong Kong or Taiwan movies with a Pink Floyd soundtrack (Updated January 2019):

| April Fool | Come in Number 51, Your Time is Up - Zabriskie Point |

| Bedevilled, The | Echoes - Meddle |

| Deadly Chase, The * |

(aka Zhui sha, Impact 5, Karate Motos - 1973) Mudmen - Obscured By Clouds (* added by ShawFan17) |

| Chinatown Capers |

The Grand Vizier's Garden Party – Ummagumma When You're In - Obscured By Clouds |

| Delinquint, The |

The Grand Vizier's Garden Party – Ummagumma Astronomy Domine - Ummagumma |

| Fist of Unicorn * | One of These Days - Meddle (* added by: OldPangYau.) |

| Gambling For Gold |

The Grand Vizier's Garden Party - Ummagumma Astronomy Domine - Ummagumma Atom Heart Mother - Atom Heart Mother |

| Happenings, The |

Echoes - Meddle Absolutely Curtains - Obscured By Clouds |

| Hunchback, The | One of These Days - Meddle |

| Kung Fu Inferno | Echoes - Meddle |

| Legends of Lust | Heart Beat, Pig Meat - Zabriskie Point |

| Marianna * |

(aka Bin Mei, 1982) Obscured By Clouds - Obscured By Clouds (* added by Panku) |

| Ninja Warlord * |

Echoes - Meddle One Of These Days - Meddle (* added by Dithyrab) |

| Operation White Shirt |

Time - Dark Side of the Moon On the Run - Dark Side of the Moon |

| Pier, The |

Time - Dark Side of the Moon |

| Roaring Lion, The | One of These Days - Meddle |

| Tales of Larceny | Careful With That Axe, Eugene |

| Tiger Jump |

Time - Dark Side of the Moon |

| Training Camp | Atom Heart Mother - Atom Heart Mother |

| Wits to Wits * |

(aka Lang bei wei jian , From China with Death, Con Man and the Kung

Fu Kid) Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun - A Saucerful of Secrets (* added by Jimbo) |

| Young Rebel, The |

Time - Dark Side of the Moon On the Run - Dark Side of the Moon |

So prepare a big bag of popcorn if you want to check these out.

Update November 2022: many thanks to Kung Fu Fandom for mentioning our blog on their Floyd soundtrack list.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

Psychedelic Celluloid (reprise)

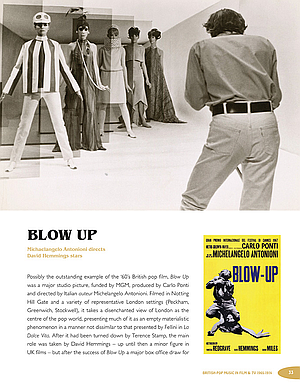

Let’s get back to Simon Matthews’ Psychedelic Celluloid. After the introduction and a chapter dedicated to Pink Floyd the main bulk of the book consists of a chronological listing of about 120 movies, starting with Richard Lester’s The Knack (1965) and ending with Stuart Cooper’s Little Malcolm and his struggle against the Eunuchs (1974), described by some as the most expensive home movie ever made as it could only be seen at George Harrison’s place.

There is nearly a movie on every page, with a picture, a short description, some info on the director, the actors and its soundtrack, but that is exactly where the cookie crumbles, as this information is almost identical to what you can already find on IMDB and Wikipedia. The author could've added more anecdotes or juicy rumours if you ask me. Take Performance, for instance, not a word about the orgies and the drugs in front and behind the camera, as Iggy Rose once testified on this holy place (see: Iggy & the Stones). But of course, books have already been written about that movie alone.

Several times when I was at the point of saying 'this is starting to get interesting' the article ends and makes place for another one, leaving my hunger unsatisfied. The intriguing story of the (disappeared) movie Popdown is a perfect example. Starring Zoot Money, with music of Brian Auger, Blossom Toes, Dantalion's Chariot, Julie Driscoll, Gary Farr and a couple of others. Its history is so fascinating that it could easily have taken six pages, but it stops at two. After reading that entry I spend a good hour browsing the Internet for more information, reading about a maniacal fan, Peter Prentice, who nearly spend a fortune trying to locate a surviving copy. Unfortunately I never found out if he succeeded in his mission, or failed. Perhaps that is what Simon Matthews really wants as I'm pretty sure he knows more about these movies than he was allowed to write. And the beauty of this guide is that it assembles a list of 120 'flower power' films in the first place.

The Pink Jungle

Pink Floyd are the uncrowned champions of the 'pop' movies during the psychedelic heyday, roughly from the mid-sixties till the mid-seventies, and that despite the fact that they even rejected a soundtrack for Kubrick. (Even more of a surprise is that Amon Düül ends second.) I count 26 Pink Floyd entries in the book and 5 for Syd Barrett. Let's have a nerdy look through our pink tinted glasses, shall we?

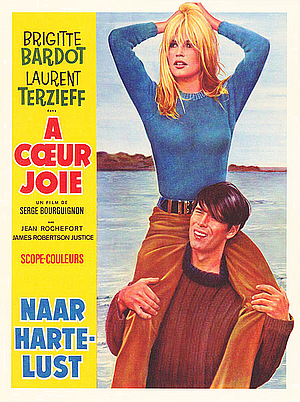

À Coeur Joie (1967), aka Two Weeks in September

This movie is only mentioned in one of the appendixes of the book. Starring Brigitte Bardot it is the story of a model, with a photo shoot assignment in London, who has to choose between her husband and a much younger passionate toy boy. This was Bardot's first attempt to excel in a serious movie, away from the sex kitten romantic comedies she had done before. Probably that could be the reason why the public didn't want to see it, but critics say the movie tried to look sophisticated but ended up pretty dull. Next to BB two English popstars play a small role: Murray Head and Mike Sarne, who had a number one hit in 1962 with Come Outside.

In a 2015 BBC documentary 'Wider Horizons' it was revealed that David Gilmour sang two tracks for the movie, composed by Michel Magne: Do You Want To Marry Me? and I Must Tell You Why. This was before he joined Pink Floyd and that is perhaps why Psychedelic Celluloid isn't aware of this.

The Holy Church Tumblr blog has several links to the songs and the movie itself: À Coeur Joie.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

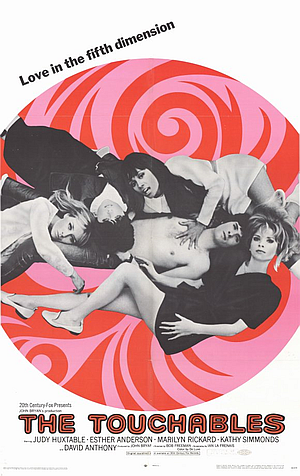

The Touchables (1968)

Simon Matthews throws an ace with the news that The Touchables has Interstellar Overdrive during one of its scenes, something that – as far as I know – has never been put in a Floydian biography before. It is one of those thirteen in a dozen, throwaway, sex comedies with a plot 'thinner than a paper towel'.

Four good-looking beauties, who like to walk around in their underwear and who are literally living in a bubble, kidnap a wax sculpture of Michael Caine and then repeat the act with a popular pop singer, whom they abuse as a sex slave, not that he resists a lot. After having a go at the four of them he finally tries to escape but they shoot him down. The situation looks grim for a minute, but even that can't spoil the fun. It all looks like one of the less interesting Monkees shows.

Add a subplot with a few gangsters and, for an incomprehensible reason, some professional wrestlers and you have a product that creates immediate amnesia after watching it.

The story was written by Donald Cammell who would later enlarge some of its situations for Performance.

Dumb movie. Great find.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

The Committee (1968)

The Committee entry has one of Mick Rock's pictures with Syd Barrett standing in front of his Pontiac Parisienne - more of that car later (obviously) - which I found a bit weird, even for a Barrett buff like me.

Then it occurred to me that Barrett had first been asked to compose its soundtrack, without the Floyd. The reason is not entirely clear, maybe Barrett was thought to be cheaper than the entire band, maybe Peter Jenner wanted to give Syd's solo career a boost (although he was officially still in the band), maybe it was believed that Syd would better understand the movie's philosophy, inspired by the theories of R.D. Laing. Whatever...

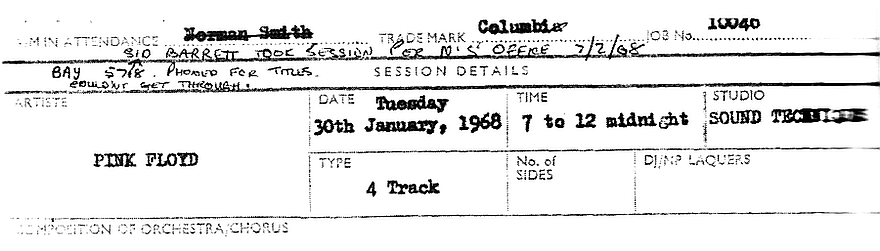

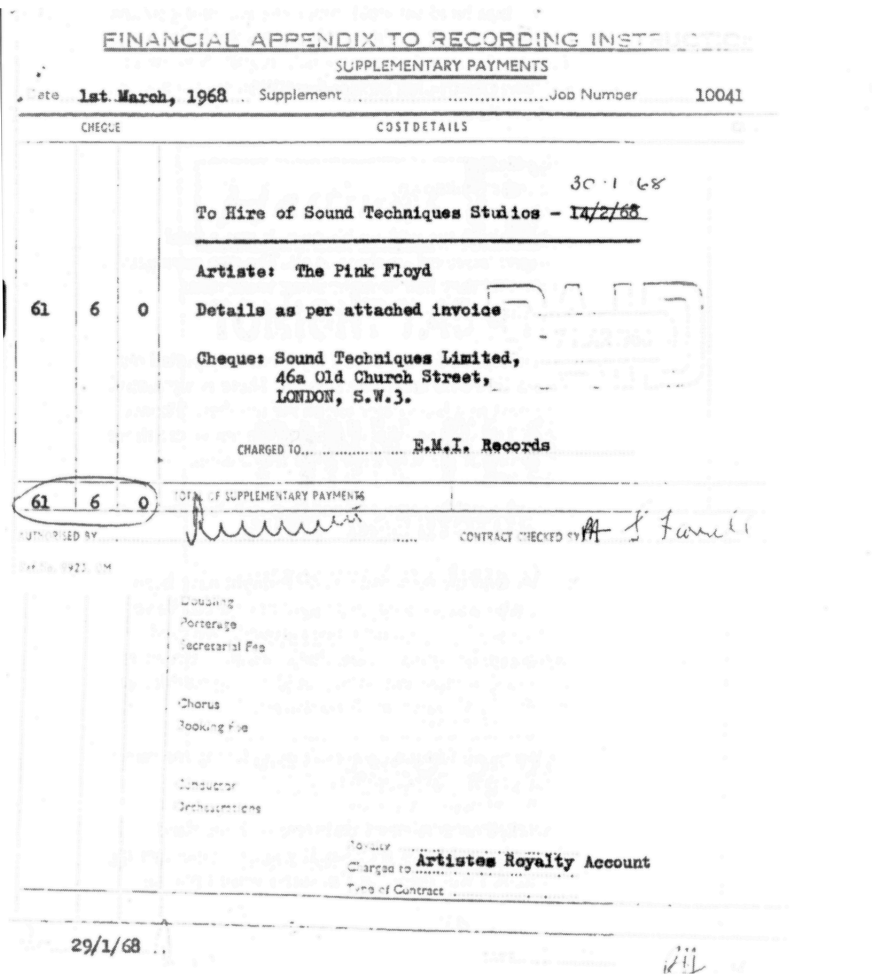

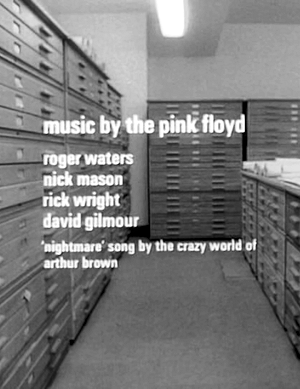

On the 30th of January 1968, a couple of days after the Floyd – now with David Gilmour - 'forgot' to pick Syd up for a gig, he arrived one and a half hour late at Sound Techniques without a guitar and without a band. A guitar was found, Nice-drummer Brian 'Blinky' Davidson and Barrett-buddy Steve Peregrin Took were presumably called in and five and a half hours later a twenty minutes music piece was in the can. Unfortunately Barrett thought it sounded better backwards so at midnight they called it a day and all went home.

The collaboration with Barrett was stopped because his studio time was too expensive and their budget was practically zero. Syd didn't show any further interest for the project either and when a studio employee tried to phone him there was 'nobody home'. Roger Waters heard about the fiasco and agreed to do the soundtrack with the rest of the band, minus Syd, in an improvised studio for practically nothing. Max Steuer in Sparebricks:

The address was 3, Belsize Square, London NW3, the basement flat of the painter Michael Kidner and his wife Marion. (…) It was amazingly professional.

Steuer remembers that Syd's piece was 'jazzy, with a groove' and that Peter Jenner took the tape with him. In 2014 we asked Jenner about the whereabouts of this 'holy grail'. Peter Jenner in The Holy Church of Iggy the Inuit innerview:

As far as I know I am not in possession of these tapes, I might have been given a copy, but surely not the masters. (…) Many things disappeared with the sudden collapse of Blackhill. My recollection is that they were less than amazing. However if I come across anything I will let you know.

The Committee is now part of Pink Floyd's Early Years box set, without – of course – the Syd Barrett tape. Unfortunately Psychedelic Celluloid was already in the can when that set was released and several times the author states that a Pink Floyd soundtrack has not been officially released, while some of it can now be found on the luxury box set.

Update 2017: in our next article we dig deeper into The Committee soundtrack, with a remarkable theory from Simon Matthews: The Rhamadan – Committee Connection

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

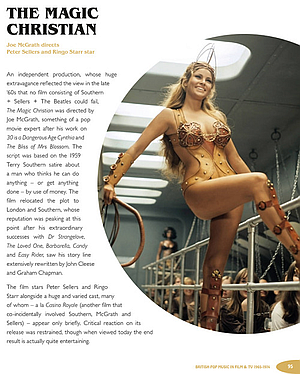

The Magic Christian (1969)

There is no immediate link with Pink Floyd in The Magic Christian, but Gretta Barclay and her boyfriend Rusty Burnhill worked on it. Gretta Barclay in the interview she gave at the church:

We did some film extra work for The Magic Christian. I have a feeling Iggy came with us? But I cannot confirm this.

As the movie was shot in March 1969, Iggy could indeed have been around. It wouldn't be the first time that Iggy was on a film set, nor the last. Another Syd Barrett friend made it even in front of the camera. One of Raquel Welsh's topless slave girls in the galleon scene was none other than Jenny Spires, but she didn't make it to the final cut, so don't ruin your eyes looking for her.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

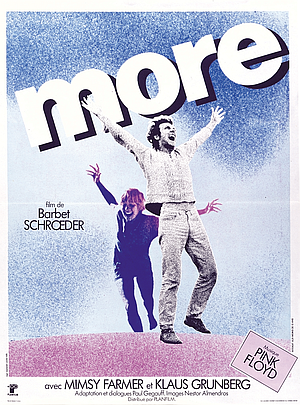

More (1969)

How could we forget More? This Barbet Schroeder movie follows the hippie trail to Ibiza, but instead of sea, sun and illicit sex it adds the deadly ingredient of heroin. Pink Floyd wrote the soundtrack.

There are some differences between the music on the album and the songs in the movie. 'Main Theme' lacks some guitar and 'Cymbaline' has alternate lyrics and is sung with a 'head voice'. The movie also contains a short instrumental 'Hollywood' that is not on the album. The Early Years compilation includes an early version of this track, titled 'Song 1'.

The song that has made fans go crazy for almost five decades is 'Seabirds'. It is a pastoral hymn à la Grantchester Meadows, but unfortunately it can only be heard during a party scene in the film. When Pink Floyd announced that 'Seabirds' was included in The Early Years box this was considered as one of those great revelations everyone was hoping for. Unfortunately the song in the box was not 'Seabirds', but an alternate take of the instrumental Quicksilver. Apparently the master tape of the 'real' Seabirds was given to the movie producers who used it for their final cut and who destroyed the only copy afterwards.

Seabirds is probably lost forever. (For our critical review of The Early Years compilation, see: Supererog/Ation: skimming The Early Years.)

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

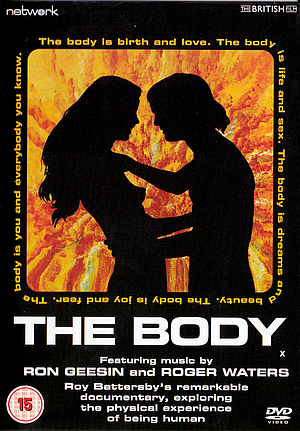

The Body (1970)

Simon Matthews overzealously implies that Pink Floyd did the soundtrack for The Body, although it was a co-operation between Ron Geesin and Roger Waters (who can be found on 8 tracks of 22). One of these, Give Birth To A Smile, was recorded with the entire band, but it was credited as a Roger Waters solo effort. (Give Birth To A Smile was considered for inclusion on The Early Years box, but at the end it didn't happen.)

Psychedelic Celluloid also states that:

The majority of the music was assembled from sounds made by the human body – burps, farts, coughs, sneezes, heartbeats, human voices, general stomach noises, etc. (p. 132)

This is only the case on two numbers (from 22), Our Song and Body Transport.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

Entertaining Mr. Sloane (1970)

Described by the author as a considerable tour de force of bad taste he rightfully notes that Georgie Fame wrote the soundtrack, but he fails to say that the most important actor of the film, a Pontiac Parisienne with numberplate VYP 74, first belonged to Mickey Finn and later to Syd Barrett. It would have been a fun anecdote.

Check some pictures of the movie on our Tumblr page: Entertaining Mr. Sloane.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

La Vallée (1972)

During the making of the soundtrack of La Vallée, so tells us Nick Mason, there was a (financial) misunderstanding between Pink Floyd and the film company. The band removed the title from the album and called it Obscured By Clouds instead. But for once Pink Floyd didn't have the last laugh as the movie was immediately sub-titled Obscured By Clouds for the English market.

Perhaps the weirdest thing is that Matthews finds La Vallée (Obscured by Clouds) a well made film with excellent photography. That last one is certainly true but most of the world is still trying to find out what the hell the story was all about. La Vallée regularly makes it into 'worst movies of all times' lists.

Throughout Psychedelic Celluloid the author duly notes when a rock or pop star occupies a (minor) role in a film. However, for La Vallée he overlooked the fact that Miquette Giraudy, wife of Steve Hillage, member of Gong and System 7, is playing the part of Monique.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

Listomania

The last part of the book has several entries that didn't make it to the

central part, for one reason or another.

Appendix 1 (fiction)

mentions Zabriskie Point, not a London based movie, and the French À

Coeur Joie (see above).

Appendix 2 (documentaries

and concert films) has Pink Floyd in Dope (1968) and Sound Of The City

(1973).

Appendix 3 (shorts) lists Peter Whitehead's London '66-'67

with Pink Floyd playing the 14 Hour Technicolour Dream.

Appendix 4

(TV specials, documentaries & concerts) mentions the Belgian 'Pink

Floid' special that has been unfortunately released on the Early Years

with the wrong soundtrack.

One category that can't be found in this pretty coherent and detailed work are the many (perhaps too many) underground and avant-garde movies, for instance from the London film-makers' co-operative LFMC, started in 1966 by Stephen Dwoskin, Bob Cobbing and others in the legendary Better Books shop. Carolee Schneemann's Viet Flakes (1965) that puts happy pop songs over Vietnam images isn't there, nor is Malcolm Le Grice's Berlin Horse (1970) with a Brian Eno soundtrack and – oblesse oblige - neither is Iggy, Eskimo Girl from Anthony Stern that has See Emily Play. But avant-garde art movies probably belong more in specialised studies for a specialised clientele (and at special rates, Oxford University wanted me to pay £119 to consult an article).

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

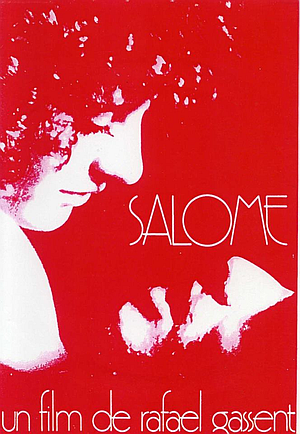

Salome (1970)

On three different occasions Simon Matthews mentions a Spanish movie that claims to include on its soundtrack a rearrangement by Jorge Pi of a Pink Floyd arrangement of Richard Strauss' Salome. Somewhat exasperated he adds 'if anyone ever finds a copy and manages to investigate'...

Well it is not that the Church didn't try.

In 1970 Rafael Gassent, the 'father' of indepent Valencian cinema, made a 51 minutes adaptation of the Oscar Wilde play and Richard Strauss opera Salomé. According to the IMDb movie database the soundtrack is composed by Richard Strauss, arranged by Pink Floyd and re-arranged by Jorge Pi.

Rafa Gasent, also known as Rafael Gassent and all combinations in between, is an experimental Spanish movie maker whose 23 and some movies are even more difficult to track down than those of Anthony Stern. Salome was allegedly shot in the Sagunto castle, inspired by the Andy Warhol school of filming and is apparently a blend of the hippie era and Spanish avant-garde 'grunge' from the early seventies. No wonder that these experimental directors weren't liked by general Franco and his Opus Dei cohorts and that these movies were only shown in underground clubs. Rafael Gasent would later work for Spanish television and his cinematographic work is now and then shown on movie festivals.

Obviously the Holy Church tried to find out what this 'arranged by Pink Floyd' means at the end credits of the Salome movie, but we couldn't find a copy to check if it is really there or not.

The Church also asked Rafael Gasent Garcia for information, in English and in Spanish, but unfortunately posting holiday pictures is a more interesting activity for him than sparing a minute for some quick comment.

So until somebody clears this up, there is a kind of enigma here. Unless...

Update 2019 05 18: The reason why this movie can't be found nowadays is because all copies were seized by the Spanish censorship administration in the nineteen seventies. For an update, please check: Salome Unveiled.

Pinfloy

This doesn't mean that the Church doesn't have a theory. Personally I think it was nothing but a youthful joke, like the Spanishgrass hoax, and that Gasent didn't use Pink Floyd as a bandname but 'pinfloy' as a noun.

Just like the Dutch language had the term 'beatle' in the sixties, for a long-haired no-good (my mother used it all the time to shout at me), the term 'pinfloy' was introduced in Andalusia in the seventies as an equally pejorative term. A 'pinfloy', to paraphrase Antonio Jesús, is somebody who acts silly, crazy, or who is quite gullible, naive and/or a bit rare.

In underground and artistic circles however, 'pinfloy' may have been re-appropriated and stripped from its derogatory meaning although it was still used for alternative people from the wackier side of the spectrum.

If Jorge Pi (or Jordi Pi) is indeed the musician of the Desde Santurce a Bilbao Blues Band, as Simon Matthews writes, this all starts to make sense. The DsaBBB were a satirical band, who weren't from Bilbao to start with and who didn't play the blues either. The band mixed rock, charleston, folk, tango and forms of classical music, combined with humorous lyrics. This was not always appreciated by the Franco regime and in one case they were even arrested.

So, to get this over with once and for all, the Salome soundtrack may not contain a Pink Floyd arrangement but a Jorge Pi 'pinfloy' treatment of Richard Strauss, meaning that the Richard Strauss melody was given a goofy swing.

Case closed then, unless somebody else comes up with a more coherent theory.

Salomé 1970 -2017

Around 2015 Gasent revised, re-imagined and reconstructed a new version of this lost movie, using material that could be traced back in several archives. The 18 minutes short (14 minutes without credits) was shown on the Mostra de València - Cinema del Mediterrani festival in October 2018 and has been published on YouTube as well.

The Holy Church of Iggy the Inuit has written an article about this version at: Salome Unveiled.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

Psychedelic Celluloid (conclusion)

Psychedelic Celluloid is an excellent vade mecum, a quick reference book, for those that are interested in the interplay of British bands and movies of the psychedelic years. The description of the individual titles could have been more detailed at points, but somewhere I have the feeling that the author wants us, the reader, to move our lazy ass and go look for it ourselves. As a whole, bringing these 120 titles together in one volume is already a gargantuan task. Mission accomplished then.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

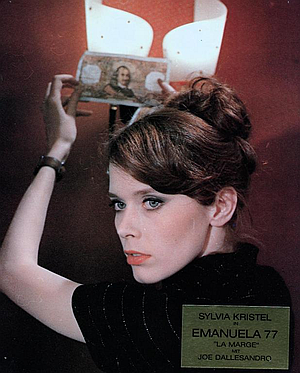

La Marge (1976) aka The Streetwalker, aka Emmanuelle '77, aka Emanuela '77.

Here is a movie that isn't mentioned in Psychedelic Celluloid, for obvious reasons. First: the setting takes place in Paris, not in London. Second: it was made outside the 'swinging London' decade, covered in the book. Still it is a must-see for people who want to know more about Floyd in film.

There is a French comedy about a film director who sells his dramatic script to a movie studio and finds out that he is expected to make a porn flick instead. This is exactly what happened to Walerian Borowczyk whose filmography evolved from art-house avant-garde to European soft-core, including the almost parodical Emmanuelle V in 1986.

Borowczyk started with ingenious stop motion and animations and shocked the public (and the censors) with the live action Immoral Tales (1974), The Story of Sin (1975) and The Beast (1975), movies that acquired a cult status and that placed him next to contemporary directors as Stanley Kubrick and Roman Polanski. These directors didn't avoid experiment either but were popular while Borowczyk was only known to a small circle of critics and movie buffs. For his next production he wanted to go for something less shocking and more accessible...

All the necessary ingredients for a successful product were there:

•

Andy Warhol superstar and beautiful boy Joe

Dallesandro, hot in France after appearing in Serge Gainsbourg's

movie Je

t'aime moi non plus, was hired for the male lead role.

• Sylvia

Kristel was the female lead. Although remembered as a sex-goddess,

she was actually an excellent much-wanted actress and Europe's

box-office queen (thanks to the Emmanuelle franchise).

• A top-score

soundtrack was assembled with French songs, old and new, and

international hits by 10CC (I'm Not In Love), Elton John (Saturday

Night's Alright (For Fighting)), Sailor (Glass of Champagne) and Pink

Floyd (Shine On You Crazy Diamond).

• Bernard

Daillencourt was the cinematographer and his work for Borowczyk was

so appreciated that David Hamilton hired him for his flimsy but utterly

lucrative erotic trilogy: Bilitis, Laura and Tendres Cousines. Actress

Camille Lariviere would also figure in Bilitis.

• The original novel,

from writer André

Pieyre de Mandiargues, had won the Prix

Goncourt for the best novel of 1967. He had also written The

Girl on a Motorcycle, put to film with Alain Delon and a young

Marianne Faithfull.

Warning: spoilers ahead.

La Marge is a dramatic mixture of love, death, adultery, suicide and full frontal Euro-chic. A rich and handsome vine-grower, madly in love with his family, visits a brothel on a business trip to Paris. After the obligatory nookie he receives a letter that his son has drowned in the swimming pool and that his wife has taken her own life. Instead of returning home for the double funeral the widower tries to cope with the tragedy by visiting the prostitute who feels that something basically has changed in his, and her, attitude.

About everything was present to make this movie the autumn box-office hit of 1976 but La Marge sank without a trace. The blowjob scene, with Shine On You Crazy Diamond on the background, should have been tattooed in our brains, like Marlon Brando's butter extravaganza in Last Tango In Paris. To cash in on Kristel's fame the movie was renamed (and re-dubbed) as Emmanuelle '77 (or Emanuela 77) but that only added to the confusion. It has been rumoured that new scenes, filmed by another director without the knowledge of Borowczyk, were added for an American cut, known as The Streetwalker, but nobody has ever managed to compare both versions.

The soundtrack, with 10CC, Elton John and Pink Floyd, may have been the reason why the movie has never became a cult classic in later years. Pink Floyd's legal stubbornness, so is whispered, has prevented a general release on DVD. A Japanese version does exist, with several blurs at strategic places, and there also floats a French Canal+ copy around, omitting a few (voyeuristic) scenes.

The Holy Church of Iggy the Inuit Tumblr has some pictures: La Marge.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

Kindle rant

While I would give the book Psychedelic Celluloid a seven rating (out of ten) for its contents, I am somewhat disappointed in the Kindle edition.

The book, as a traditional book, is beautifully printed, with a lot of white-space next to the text to include pictures in a separate column or to interact with the text as in the 'Magic Christian' example at the left.

However, the Kindle version does not allow in-text searching, nor adding notes, nor changing the font size. On my medium sized tablet screen (10.81 by 6.77 inches / 27.46 × 17.20 cm) the letters are the size of miniature ants due to the fact that every page can only be shown in its entirety. The picture legends have golden letters on a white background and are completely unreadable (you can't change the background colour either, as in other Kindle books).

Reading the Kindle version of Psychedelic Celluloid is like reading a badly xeroxed book but with the one difference that on good old photocopies you could still scribble some notes.

I would like to say to Oldcastle Books and/or Amazon this is a fucking disgrace and that you only bring the author's reputation down with this kind of crap.

Still a good book though.

Simon Matthews

Psychedelic Celluloid

Oldcastle Books, 2016.

224

pages.

(Back to contents, top of the page.)

The Church wishes to thank: Gretta Barclay, Vanessa Flores, Stanislav

Grigorev, Rich Hall, Peter Jenner, JenS, Antonio Jesús, Göran Nyström,

OldPangYau, Panku, Dylan Roberts, Venomous Centipede.

♥ Libby ♥ Iggy ♥

Sources (other than the above mentioned links):

Jesús,

Antonio: Curiosidades

- Pinfloy, un vocablo del sur, Solo En Las Nubes, 16.09.2011.

Mason,

Nick: Inside Out: A personal history of Pink Floyd, Orion Books,

London, 2011 reissue, p. 169.

Muños, Abelard: Rafa

Gassent, director de cinema, La Veu, 07.01.2014.

Palacios,

Julian: Syd Barrett & Pink Floyd: Dark Globe, Plexus, London,

2010, p. 320.

Parker, David: Random Precision, Cherry Red

Books, London, 2001, p. 119.

Our Tumblr page contains a description of another movie with Pink Floyd music, that we deliberately didn't include here: Alex De Renzy‘s Little Sisters (1972).